|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

by Mary J. Ortner, Ph.D.

|

|

| |

|

|

Captain Nathan Hale

New England

Rangers

|

Nathan Hale was a young man who had every prospect

for a happy and fulfilling life. Contemporary

accounts indicate that he was kind, gentle,

religious, athletic, intelligent, good looking and

as one acquaintance testified, "the idol of all his

acquaintances." Both men and women commented on his

striking appearance. He had fair skin and hair,

light blue eyes, and stood just under six feet tall.

No wonder it was said that all the girls in New

Haven were in love with him. While many were

impressed by his kindness and strong Christian

ideals, he was also known for his skill in

wrestling, football, and broad jumping.

Yet in spite of the above, this remarkable young man

ended his life in the most ignominious manner known

to his era: death by hanging - the ultimate

degradation - reserved only for the most despicable

of criminals. He risked this fate willingly to serve

a cause as yet unproven or established, a cause more

likely to be soon annihilated. Nathan Hale is

representative of many young eighteenth century

professionals who were obsessed with being of

service for the public good, who - foreshadowing a

twentieth century brand of patriotism - asked not

what their country could do for them but rather what

they could do for their country.

Nathan Hale of Coventry, Connecticut was born in

1755 into two respectable New England families. His

parents, Richard Hale and Elizabeth Strong Hale,

were staunch Puritans who believed in religious

devotion, work ethic, and education. The sixth of

ten surviving siblings, he was tutored by the local

minister, Rev. Dr. Joseph Huntington, who greatly

influenced his love of learning. In 1769, both

Nathan and his brother, Enoch, were sent to Yale

College at the ages of 14 and 16, respectively. They

became part of the shining Class of 1773, many of

whom were destined to have remarkable careers in the

service of their country, their state, and their

communities.

During his college years, Nathan was exposed to the

cosmopolitan atmosphere of New Haven and to many

new, progressive ideas of the eighteenth century. It

was doubtless a different world from the isolated

farming community where he had been raised. Both

brothers belonged to the literary fraternity,

Linonia, which debated educational topics and issues

of the day - including astronomy, mathematics,

literature, and the ethics of slavery. Meetings were

held in the students' rooms at New College - a large

brick dormitory in the center of campus. This

beautiful building, where Nathan and Enoch were

roommates, still stands on the Yale campus

(Connecticut Hall). His time was full of activity,

strong friendships, and varied interests, including

helping to establish Yale's first secular library.

Nathan graduated from Yale with first honors at the

age of eighteen, participating in the 1773

commencement debate: Whether the education of

daughters be not without any just reason, more

neglected than that of sons.

Like many young graduates, Hale took a position

teaching school - first in East Haddam and later in

New London, Connecticut. In rural East Haddam,

however, Hale appears to have been lonely, missing

the lively company of his college friends. New

London was definitely more to his liking - it even

had a newspaper, liberal in character, published by

Timothy Green, a proprietor of the Union School. His

classes consisted of about thirty young men who were

taught Latin, writing, mathematics, and the

classics. In 1774, he also conducted a summer school

for young ladies from 5 to 7 AM. That the young

ladies of New London were willing to attend a 5 AM

class in the classics was perhaps more a tribute to

the schoolmaster's good looks that any attraction to

the subject at hand. Although he never appears to

have been serious about marriage, during 1774 he was

teased by two former classmates about an infatuation

with his landlord's niece, Elizabeth Adams. Although

Elizabeth married in 1775, in 1837 she wrote a

stunningly beautiful remembrance of her friend,

Nathan Hale, then dead for sixty-one years.

Nathan enjoyed teaching and his mild manner of

imparting knowledge was greatly appreciated by both

students and parents alike. Consequently, in late

1774 he was offered a permanent teaching position as

the master of the Union School and it appears that

he intended to make teaching his profession. During

this same year, he also joined a local militia and

was elected first sergeant. While his amiability

made him many delightful acquaintances among the

town's best families, nineteen-year old Nathan Hale

also continued several close friendships with his

former Yale classmates. Their surviving letters tell

of the joys, frustrations, romances, and boredom

experienced by young people on the threshold of life

and painfully impatient for it all to unfold. By the

spring of 1775 therefore, civic-minded Nathan Hale

had many interesting friends, a great job that he

enjoyed, perhaps a girl friend (or more), and an

enjoyable life in a bustling cosmopolitan seaport

city. Everything was going his way.

When war broke out in April, many chapters of

Connecticut militia rushed to Massachusetts to help

their neighbors during the Siege of Boston. Hale's

militia marched immediately but he remained behind -

perhaps because of his current teaching contract

which did not expire until July, 1775. Or perhaps he

was unsure. Contemporary letters tell of the

conflict that went on in his friends' minds -

doubtless mirrored in his own - whether to join the

new army and fight in Boston or to keep quiet and

wait. This was not the clear decision we all see

today and these young professionals had a lot to

lose. The new master of a prestigious private school

does not without considerable risk take on the label

of rebel and traitor.

In July 1775, Nathan received a heartfelt letter

from classmate and friend, Benjamin Tallmadge.

Always the pragmatist, Tallmadge had gone to see the

Siege of Boston for himself. Upon his return, Ben

poured out his heart in a letter to Nathan dated

July 4, 1775 - the last year that date would be just

another day. After analyzing the pros and cons of

joining up, Tallmadge finally told Nathan that, in

spite of his friend's engagement in a noble public

service (teaching school), "Was I in your condition

... I think the more extensive Service would be my

choice. Our holy Religion, the honour of our God, a

glorious country, & a happy constitution is what we

have to defend." The day after receiving Tallmadge's

letter, Nathan Hale accepted a commission as first

lieutenant in the 7th Connecticut Regiment under

Colonel Charles Webb of Stamford.

Stationed at Winter Hill, Hale enjoyed military life

and threw himself wholeheartedly into the duties of

a company commander, trying to be a good officer,

yet yielding to and clearly enjoying the new, macho

experiences of camp life. Like most young soldiers,

he complained about his superiors and worried about

his subordinates - on one occasion offering his own

salary to his men if they would stay in the army

another month. Still - he told his friends - he was

enthusiastic, happy to be there, and wouldn't accept

leave even if he could get one.

When Washington reorganized the army, Nathan

received a captain's commission in the new 19th

Connecticut Regiment and - to his credit - several

men asked to be placed under his command. In the

spring of 1776, the army moved to Manhattan to

prevent the British from taking New York City.

Nathan spent six months at Bayard's Mount building

fortifications and preparing for the inevitable

battle. When the British invaded Long Island in

August, 1776, Hale had still not seen combat and his

regiment also missed fighting in the Battle of Long

Island. After almost a year in the army, he had kept

records, drawn supplies, written receipts, and

supervised guard duty. These were not the daring

exploits young men dreamed of when they went to war.

At the beginning of September 1776, with the British

in command of Western Long Island and the rebel army

trying to defend Manhattan, Washington formed The

New England Rangers, an elite, green beret-type unit

under Lt. Col. Thomas Knowlton. Hale was invited to

command one the four companies assigned to forward

reconnaissance around the Westchester and Manhattan

shorelines. Meanwhile, Washington desperately needed

to know the site of the upcoming British invasion of

Manhattan Island. The best way to obtain this

pivotal information was to send a spy behind enemy

lines but in honor-conscious eighteenth century

minds, spying was considered to be a demeaning,

dishonest, and indecent activity - unworthy of a

gentleman.

Nevertheless, Knowlton persuaded Nathan Hale to

volunteer for this spy duty behind enemy lines.

Before leaving, Nathan asked his fellow officer and

friend, Captain William Hull, for advice. Hull tried

hard to dissuade him from the dangerous and

controversial mission but in the end Nathan

justified it by saying that any task necessary for

the public good became honorable by being necessary.

This was finally his chance to do something valuable

to the patriot cause.

Accompanied by his sergeant, Steven Hempstead, Hale

left Harlem Village in early September and headed

north along the East River. Although armed with an

order allowing him to commandeer any armed American

vessel, Hale was prevented from crossing to Long

Island by numerous British ships on patrol. He

finally found passage at Norwalk, Connecticut and

crossed the Long Island Sound in a rebel longboat.

Leaving his uniform, commission, silver shoe buckles

and other personal possessions with Hempstead,

Nathan Hale slipped into the darkness at Huntington

Bay, Long Island and dropped out of sight - both to

his friends and to history.

He doubtless spent several days behind enemy lines

in his contrived disguise as an schoolmaster looking

for work. Before he could return with any useful

information, however, the British invaded Manhattan

at Kip's Bay (East River at 34th Street), taking

most of the island on September 15th and 16th. His

mission negated, Hale may have crossed into

British-occupied New York City presumably to gain

whatever intelligence he could for Washington, who

was now entrenched behind the bluffs at Harlem

Heights. On September 20th, New York City was set on

fire, causing confusion, rioting, and a heightened

alert for rebel sympathizers. By this time, Hale is

thought to have returned to Long Island for a

planned rendezvous with the longboat. On the evening

of September 21, 1776, he was somehow stopped,

perhaps near Flushing Bay, Long Island, by the

Queen's Rangers, a new company of Loyalists led by

Lt. Col. Robert Rogers (of Northwest Passage fame).

The circumstances of his capture have never come to

light although many theories have been proposed.

Almost immediately after Hale's death, rumors flew

that he had actually been recognized while

undercover by his first cousin, Samuel Hale, a

dedicated Loyalist then working for the British in

New York. Samuel denied these allegations and what

part, if any, he had in his cousin's fate has never

been substantiated.

Nathan Hale was immediately brought for questioning

before the British commander, General William Howe,

who had just moved into the Beekman Mansion (51st

Street and 1st Avenue). Intelligence information was

found on his person and since this was not in code

or invisible ink, he was irrevocably compromised.

Hale identified himself, his rank, and the purpose

of his mission, perhaps to regain a semblance of an

honest soldier (rather than a spy). Although Howe

was moved by the young man's demeanor and

patriotism, he was out of uniform behind enemy

lines. The customs of war were clear and Nathan was

sentenced to hang the next day.

A tradition says that Hale spent the night confined

in a greenhouse on the Beekman estate and that he

was denied a minister or even a bible by the provost

marshal, an unsavory character named William

Cunningham. The next morning, Sunday, September 22,

1776 at 11:00 AM, Nathan Hale was marched north,

about a mile up the Post Road to the Park of

Artillery. It was located next to a public house

called the Dove Tavern (66th Street and 3rd Avenue),

about 5 1/2 miles from the city limits. After making

a "sensible and spirited speech" to those few in

attendance, the former schoolteacher and Yale

graduate was executed by hanging - an extremely

ignominious and horrible fate to one of his time and

class.

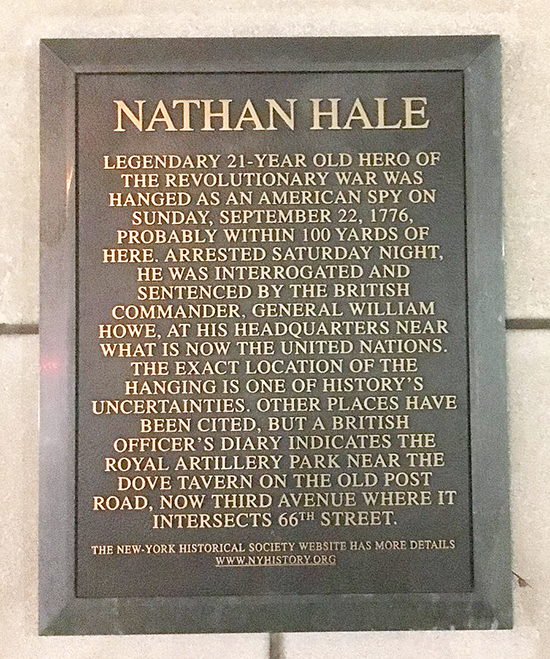

Location of Hale's

hanging in modern-day New York:

Whether Hale said that he only regretted having one

life to lose for his country has been debated. The

quote comes from a British engineer, John Montresor,

who kindly sheltered Nathan in his marquee while

they were making preparations for the hanging. Hale

entered and appeared calm, asking Montresor for

writing materials. He then wrote two letters - one

to his favorite brother and classmate, Enoch Hale,

and the other to his military commander (these

letters have never been found and were probably

destroyed by the provost marshal).

Captain Montresor witnessed the hanging and was

touched by the event, the patriot's composure, and

his last words. As fate would have it, Montresor was

ordered to deliver a message from General Howe to

Washington (under a white flag) that very afternoon.

While at American headquarters, he told Alexander

Hamilton, then a captain of artillery, about Hale�s

fate. Captain Hull found out and went with the

delegation returning Washington's answer to Howe

whereupon he managed to speak with Montresor. The

British engineer told Hull that Nathan had impressed

everyone with his sense of gentle dignity and his

consciousness of rectitude and high intentions.

Montresor quoted Nathan's words on the gallows as:

"I only regret that I have but one life to lose for

my country."

This elegant statement, doubtless paraphrased from

Addison's popular play, Cato, is the quotation best

remembered from the execution of Nathan Hale. He

must have been telling the British that his cause

still had great merit and that someone like himself

- intelligent, educated, and decent - was willing to

die for it without regret. It should be put in

prospective that the cause was in bad shape in

September 1776. The much-defeated and demoralized

rebel army had been chased into upper Manhattan,

ripe for total destruction by the vastly superior

British forces. Its soldiers were deserting in

droves now - sometimes whole companies at once - and

the end seemed only a matter of time. But Hale told

the British straight - standing on the gallows -

that his country was still worthwhile and worth

dying for.

William Hull later told the world about his friend�s

patriotism, bravery, and sacrifice; however, since

Hull's account is not that of an eyewitness, many

historians have denied his story as a

unsubstantiated folk legend. If this is true, it

means that either Montresor or Hull lied about

Hale's last words, which seems like a strange thing

for either of them to do. From a practical

standpoint, it is hard to believe that Hale would

have been so well remembered had he not

distinguished himself in some outstanding manner at

his execution. He was a junior officer of no

significance and even his brief spy mission had

failed.

Another credible statement purporting to be from

Nathan Hale's execution is found in the diary of Lt.

Robert MacKensie, a British officer in New York at

the time. The diary entry was made on the very day

of Hale's execution, September 22, 1776: "He behaved

with great composure and resolution, saying he

thought it the duty of every good Officer, to obey

any orders given him by his Commander-in-Chief; and

desired the Spectators to be at all times prepared

to meet death in whatever shape it might appear."

This indicates that Hale wanted to be remembered as

a soldier under orders and not a spy.

In conclusion, an insignificant schoolteacher who

never wrote anything important, never owned any

property, never had a permanent job, never married

or had children, never fought in a battle and who

failed in his final mission - made history in the

last few seconds of this life. He is to be admired

because of his courage in accepting a difficult

mission (both dishonorable and dangerous) that he

did not have to do. Then he had the cool and

presence of mind to set the British straight about

American patriotism, literally in the shadow of the

gallows. We don't know what exactly he said, but it

must have been impressive and Hale deserves to be

remembered for his genuine dedication, his courage,

and his willingness to pay the price with honor and

dignity.

Nathan Hale's body was left hanging for several days

near the site of his execution and later was buried

in an unmarked grave. He was 21 years old."

|

|

|

|